A few weeks ago, I took a personality quiz titled, “What kind of wetland are you?” and decided that I am indisputably, without a doubt, a wet meadow. “Productivity icon. Not great at letting go. Occasionally catches fire, but it’s all good.” In other words, me.

Though the term might not be familiar, you’ve undoubtedly walked through more than one wet meadow in your life. These are the squishy fields that you schlep through in the spring – not quite marsh because there is rarely standing water, but also not quite prairie, because they never dry out fully enough for grasses like big bluestem and Indian grass to take hold. In a wet meadow, you might find native flowers like spotted joe-pye weed, touch-me-not, swamp milkweed, marsh marigold, and white turtlehead growing among sedges (sedges look like grasses but are sharper and with edges), horsetail, and shrubs. While pausing in the middle of a wet meadow to wring the water out of your socks, you might also be lucky enough to see some of the frogs, turtles, sandhill cranes, marsh wrens, and butterflies that call these places home.

In spite of their soggy nature, wet meadows are actually one of several habitat types in the upper Midwest that are considered to be “fire-dependent”. As is the case with prairies, the plants in wet meadows are able to survive periodic fires due to their deep root systems, and usually emerge with renewed vitality. Fire helps to recycle nutrients, encourage the growth of native plants, and halt the encroachment of shrubs and invasive species. Without fire, all but the wettest of wet meadows eventually fill in with trees and shrubs and become a different habitat altogether.

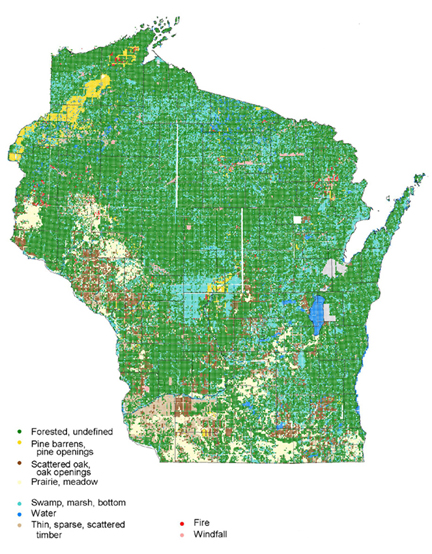

Maps of precolonial vegetation in Wisconsin show that wet meadows were often found on the western sides of large rivers, adjacent to prairie and oak savanna. On the eastern sides of the rivers, better protected from fire, the habitat was more likely to be tamarack swamp or mesic forest. Scientists have also studied peat cores from wet meadows and found charcoal fragments in many different layers of soil, which illustrates the frequent presence of fire over many hundreds of years (Davis, Wetland Succession, Fire and the Pollen Record: A Midwestern Example, 1979). Often, these fires were caused by lightning strikes, but in some locations, the native people of the region (Dakota, Anishinaabe, Menomonee, Ho-chunk) used fire as a tool to help maintain open areas for hunting and gathering food.

Today, land managers continue to use fire as a tool to restore and maintain fire-dependent ecosystems, such as prairie, oak savanna, pine barrens, and wet meadows. Prescribed fires are carefully planned to account for wind and weather conditions and are conducted by trained professionals, with a permit and approval from the local fire department. As an example, Washington County will be conducting prescribed burns this year at Big Marine Park Reserve, Cottage Grove Ravine Regional Park, Lake Elmo Park Reserve, Pine Point Regional Park, Square Lake Park, and St. Croix Bluffs Regional Park, as well as along County Road 18 in Lake St. Croix Beach.

If you’d like to learn more about prescribed fire and even watch a live fire demo, Lake Elmo Park Reserve will host a Prescribed Fire Open House on Tuesday, April 2, 4-7pm at the Nordic Center Trailhead. At the event, you can learn about the tools and safety protocols used to conduct prescribed fires, watch a live fire demo, talk to experts, and find resources to help restore native habitat on your own land as well.

Partners for the event include Washington County Parks, Dakota County Parks, City of Lake Elmo Fire Department, Washington Conservation District, Pollinator Friendly Alliance, and The Prairie Enthusiasts.

Great blog post Angie! Millions of acres of Minnesota’s native plant communities are fire dependent — from wet meadows to northern forests. The fire needs across Minnesota have been quantified in the recent Minnesota Fire Needs Assessment available at https://www.mnprescribedfire.org/mnfireneedsassessment. We could be burning millions of acres annually to maintain and enhance ecosystem integrity. Please consider sharing this Fire Needs Assessment at your April 2 open house! Thanks for your work!

LikeLike

Thanks so much for sharing this Lane! I think you’re also going to be talking with my colleague Barbara Heitkamp soon and we’re wondering if you or someone else from the Minnesota Prescribed Fire might be able to help us put on a landowner skills training this fall (half day workshop) for the many people in Chisago and Washington County that have restored prairie on their land.

LikeLike

Hi Angie,

It sounds like you’re working with Jason Andersen of Pheasants Forever. Jason is part of the Steering Committee for the MNPFC and is currently serving as our secretary. So, you’re already connected to the Council! If it’d be helpful for us to connect and exchange information related to your autumn plans, let me know! There may be ways I can provide support.

Thanks for your efforts,

Lane — Lane Johnson Research Forester | Cloquet Forestry Center | cfc.cfans.umn.edu University of Minnesota | umn.edu | 218-726-6411

LikeLike